Get a beer, or something to drink, and lets chat about MEG.

Here’s what to expect over the next 15 minutes or so:

Looking at MEG’s inability to easily grow through the drillbit

Why the post-payout royalty hasn’t been digested by the equity markets

Considering their multiple, and NAV, and where it should be

Reviewing their capital return and buyback program

Briefly cover WCS and their positioning in the market

Closing it out by counter-arguing everything I’ve discussed, AKA the positives

MEG Energy is a good company; long reserve life, constantly improving balance sheet, prudent buyback strategy, and a solid asset— by any measure you could call it a free cashflow machine, but I don’t think any of that matters. MEG is an oil and gas enthusiast’s darling; with SAGD showcasing the raw engineering talent Alberta has, and over 30 years of proven production, there’s plenty of sweet bitumen to go around. But it doesn’t tick the boxes of what I believe new funds flowing into the sector will be looking for. In reality it’s still a relatively small name, without a dividend policy (buybacks force investors to double down on the stock, great for O&G lifers, not so much for others), and most importantly, no to low growth or optionality given the nature of their single Christina Lake asset. Thus, I don’t think that MEG is the best name to own over the next few years to play emerging energy themes. Longer term, MEG is certainly an attractive name to hold if you believe in the reserves trade, but in the short to medium term, it may suffer.

In the energy trade, at this stage, you either go with a junior exploration name (some may call it a ‘hail mary’), a SMID, or a senior. MEG isn’t a senior, and it’s not a very good SMID all things considered. It has an identity crisis of sorts. It can’t compound production (only add in large, capital intensive chunks), it can’t acquire like other names such as CNRL (TSX:CNQ) which has the multiple and cash to purchase; and MEG doesn’t have the torquey allure that some high growth companies offer. It’s “meh”, or middling in my books. Being able to add pads of low decline production isn’t the worst thing, after all, they have the regulatory ability to double production, but a zero free cashflow name undergoing growth (no growth is the theme de jour) is hard to sell to outside capital.

Take Kelt Exploration (TSX:KEL) for example, it’s a no to low free cashflow name focused on growth. Outside a few chunky insider and institutional positions, there is a noticeable lack of generalist capital. It trades less volume (adjusted for size) than peers, and, it’s flat on the year. It’s not a good bell weather for what the capital markets do to you when you take the free cashflow away and focus on growth. I believe that, should MEG decide to expand their current operations, a similar fate would follow. This is positive for the very long term investors, developing their reserves will have to come at some point, though at this point in the cycle they may not fare well in the equity markets should they decide to.

Inability to Grow Easily

In 3Q22, MEG hit an impressive 110kb/d of bitumen production— not bad for a facility with current nameplate capacity of 100kb/d. But that completely obliterates any hope of further asset expansion in the future without material capital expenditures. I don’t think this 10% increase in production is fully priced into the stock, but at best worth a few bucks a share. With them cresting to what should be considered peak medium term production within their current infrastructure, there is really no low-cost way for them to keep growing their Christina Lake asset given current facilities. Now, there are two schools of thought around this fact (and two thoughts I’ve battled with when thinking about the name)— is this a good thing (they can’t screw things up that badly), or a bad thing (no optionality, and no easy ability to make accretive acquisitions). I fit solidly into the camp where they should be dinged on the multiple front for having mostly no easy ability to further their business. It should also be noted that in 3Q21 on the quarterly conference call, in response to a Goldman Sachs analyst, Derek Evans said “they have no plans to grow past the current at-steam capacity”. With this in mind, I am operating under the assumption that the path forward is ‘financial’ growth through buybacks, rather than continued expansion of Christina Lake.

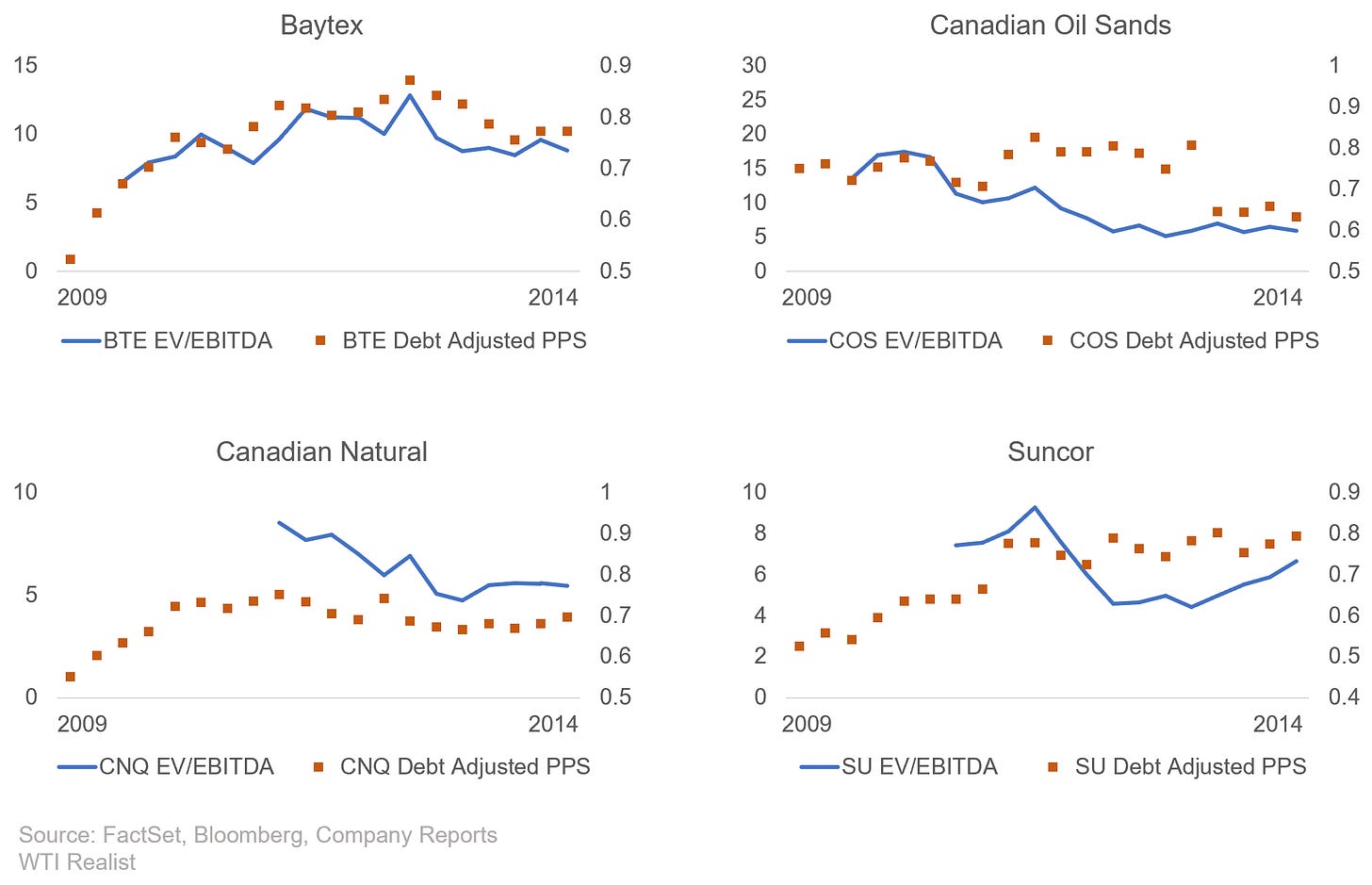

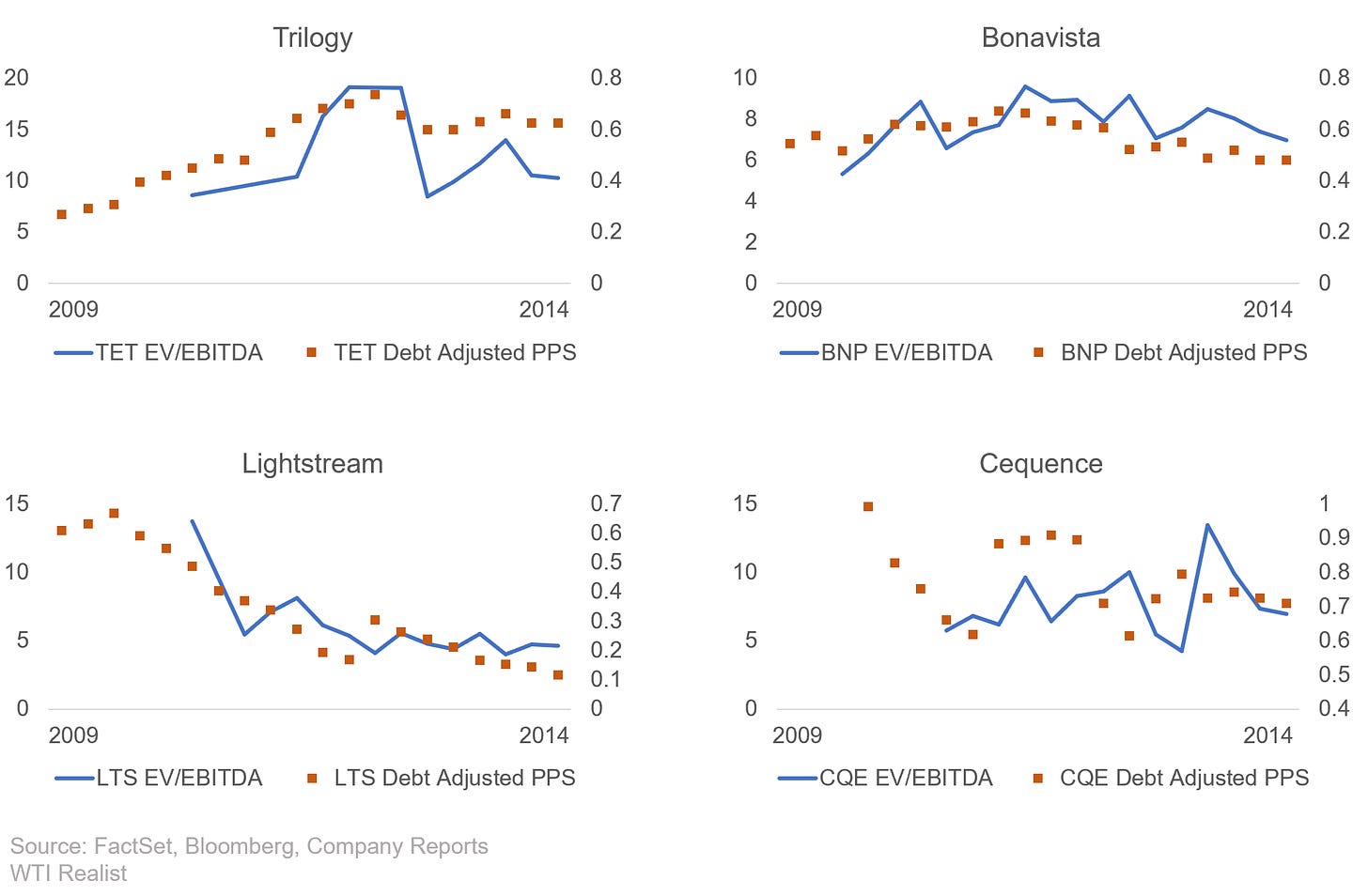

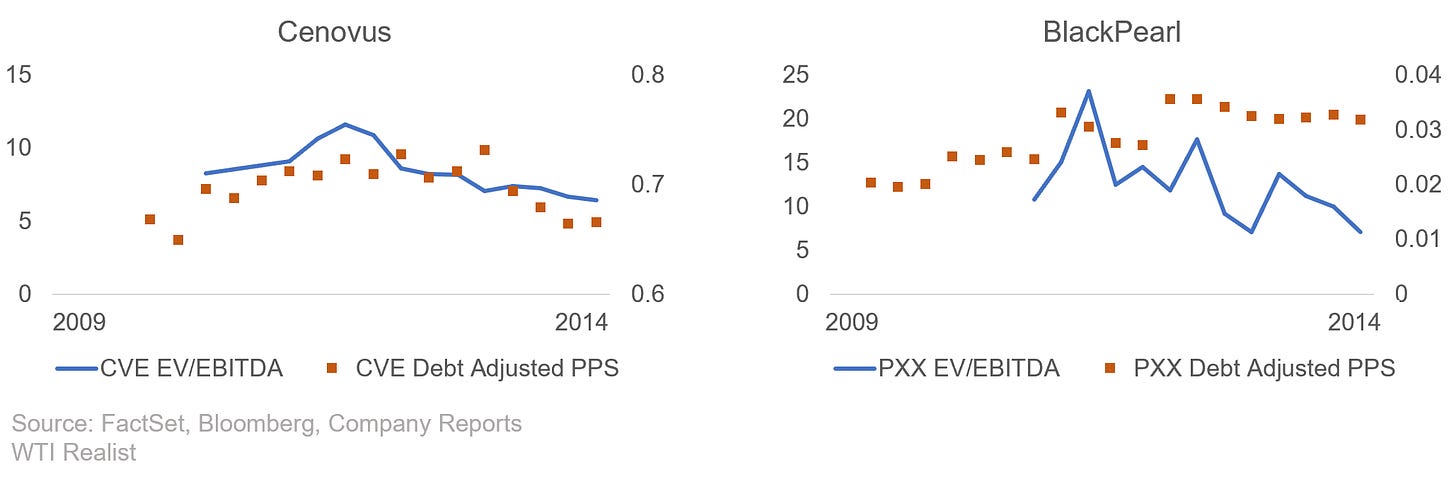

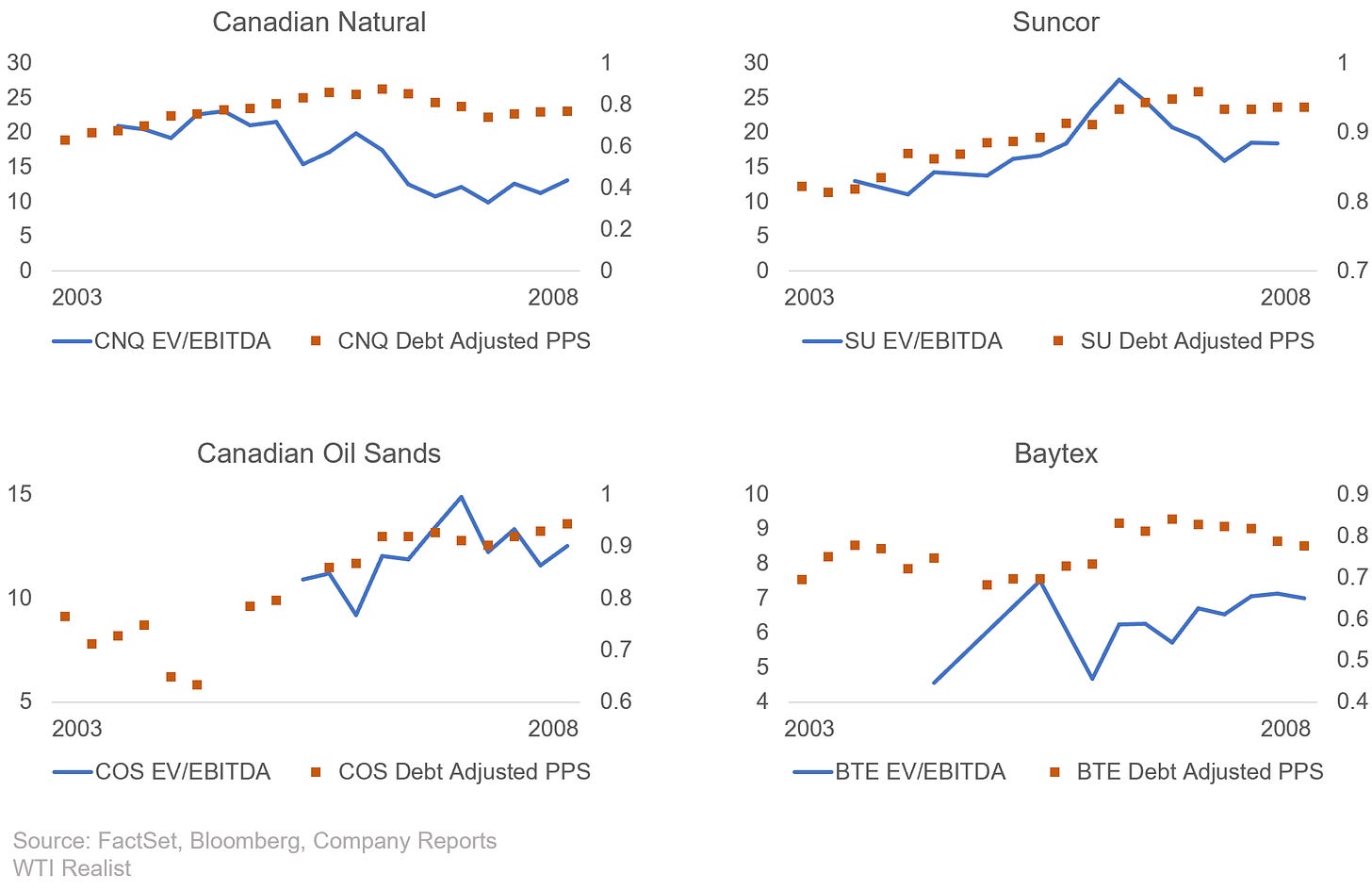

So, lets take a walk down memory lane, looking at what happened during the past few cycles. What is the correlation between expected/actual growth, and actual/terminal multiple expectations? Well, it kind of turns out there’s a decent correlation between (debt adjusted) per share growth, and multiple expectations. During previous bull markets, the correlation between EV/EBITDA multiple, and debt adjusted production per share (DAPPS) is quite apparent. It makes sense, you ‘grow into’ a multiple, and if the market believes you are going to reliably increase cashflows in the future, they pay more for those cashflows, in my view, the same idea as using a TAM value in tech, or the SaaS frenzy, just on a much more restrained scale.

The charts below track consensus EV/EBITDA (LHS) multiples across 14 names, during the last bull cycle between 2009 and 2014. There message is quite clear, if you want to drive a higher multiple, you need to perform when it comes to increasing your debt adjusted production per share (DAPPS, RHS)

Below are the same charts, with a 2003 to 2008 timeframe.

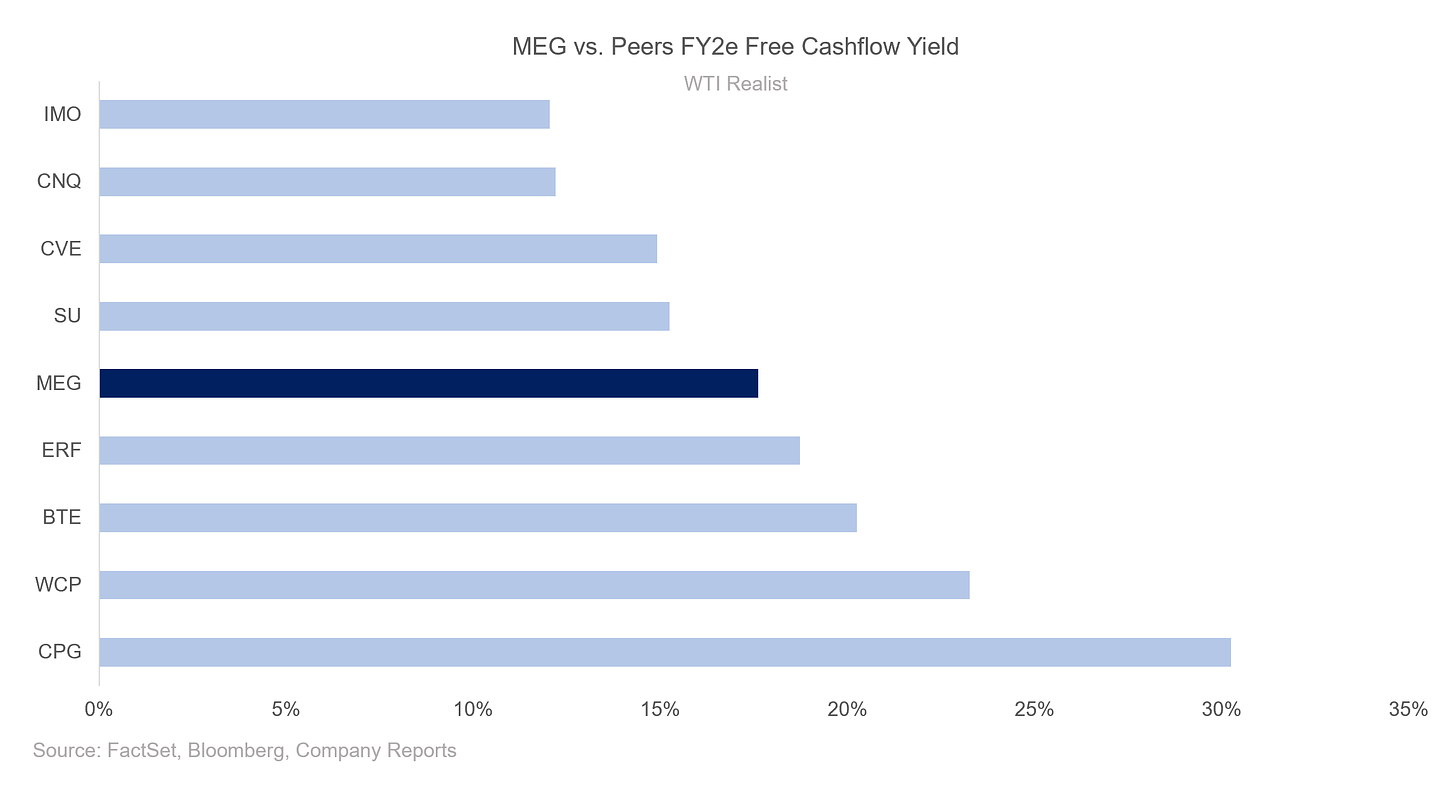

If we come back into the present day, their only mechanism to add barrels is to buy them back through their stock, but their free cashflow yield, is also quite middling. Slightly better than their integrated and senior peers (rightfully so), but significantly less than their more nimble, and less heavy oil exposed SMID peers. I get the feeling they want to be a smaller version of Imperial, but Imperial has net neutral(ish) heavy exposure through downstream operations, and a better execution track record, so why own MEG when comping against Imperial, or any of the seniors, and why own MEG when comping against proven SMIDs like ERF or WCP? Their position in the market feels shaky when participants are currently, and likely for the medium term, focused primarily on cashflow and less on NAV and reserves.

So their two options now for growth are to either start a new greenfield project (obliterating free cashflow for the capital expenditures associated with such an undertaking), or diversify beyond oil sands (likely into gassy assets as a SAGD operator is structurally short their inputs). The first option (greenfield) results in free cashflow going to zero (market will hate that), or diversification from a single asset play, which brings along its own risk, and higher costs (market reaction would likely skew negative, assuming it’s operated by them).

Of course, there’s per share paper growth they can drive through accretive buybacks, though, my main issue with MEG buybacks is it’s their only way of per share production growth (and cashflow outside of movement in the oil price). In my estimation, they are only a few bucks below their mid-cycle NAV, meaning the accretion margin (aka effectiveness) of buybacks become thinner and thinner as the equity continues to appreciate (adjusted for WCS strip and buyback movements). As a fan of buybacks for corporate capital allocation, on a super-cycle price assumption, leaving buybacks as your only way to materially drive production per share (and thus, your multiple) seems less than desirable.

New Royalty Rates

We know that Christina Lake is going to transition into the post-payout royalty regime in a few months, no doubt this is going to be a shock for shareholders.

Looking at “unexpected news” among energy names this year, even if circulated softly prior to the event, the reaction in the equity markets is almost always negative, again, even for news/events that were generally known. I don’t see MEG bucking this trend, and, don’t think that awful WCS pricing along with increasingly punitive royalty rates are going to be countered with production being a few points higher than expected.

The closest parallel to post-payout royalty rates (in my mind) is the Vermilion Energy (TSX:VET) windfall tax. It was a decision that will have a significant impact on cashflows, and it was generally known by the market ahead of time— much like MEG’s transition to post-payout status. But, in the chart below, even though we knew about the windfall tax many months in advance of their Q3 earnings, the market didn’t fully price it into the stock until we got a real print with it.